In case you have been asleep, the ICO market has cooled off.

In a new report, Juniper Research forecast another 47% sequential drop in transaction values in Q3, 2018 and warned “the industry is on the brink of an implosion.”

Against this backdrop, and for the last several few quarters, securities token offerings (STOs) have been gaining attention, and traction. It looks like STOs are going to find more support from regulatory bodies were the evolved position of seems to be that the best practice for token offerings is to assume that any offering made in the U.S. or offered to U.S. persons is a security token offering (STO), which must comply with federal and state securities laws.

Plenty of ICO evangelists and ideologues are negative on STOs. A recent critical post accuses STOs as being some kind of a trap set by the mainstream, VC and banking community as a means of wrestling back control of the capital markets.

The author levels several criticisms of STOs:

- Undertaking an STO (as opposed to ICO) is caving in to VC and institutional investor preferences for their own risk-reward models.

It is a false choice to suggest that either you stick with an ICO and the risk-reward model to offers, or you are falling in line with a risk-reward model determined by VCs and institutional investors. The fact is, most companies that raise capital under an ICO framework would not meet the quantitative and qualitative criterion VCs and institutional investors require (for every 100 deals they vet, only a small percentage actually gets a check).

And even if a business contemplating an ICO would clear the hurdles, they still have the ability to negotiate terms. They don’t have to take the money if it is not sufficiently friendly. These companies are in the driver’s seat. If they are sufficiently sexy to win an offer from a pro, they will more than likely be able to attract plenty of other offers, on terms they find more favorable.

- The STO structure is just a means of VCs and institutional investors to get some kind of equity passed through the security token.

It is untrue that the STO structure is nothing more than a way for VCs and institutional investors to get their share of equity. But even if this is one of the outcomes, is having a professional investor on board with equity really a bad thing in itself?

In more than a few cases, having a professional investor, incentivized to add value through her experience, network of resources and relationships on board can be a significant benefit – even an “unfair competitive advantage.”

“The Future of Cryptocurrency: Bitcoin & Altcoin Trends & Challenges 2018-2023.” September 10, 2018.

“The Security Token Offering (STO) – It’s a Trap!” Cal Evans. September 5, 2018.

- VCs and financial firms don’t like ICOs because it keeps them from implementing their own model which includes, amongst other things, demanding a lion’s share of issuer equity, installing their own boards and issuing shares how they see fit.

To be sure, there are horror stories about companies that have no alternative but to take capital on terms that are unfriendly, and even hostile. But if they are in this kind of position, things have been going wrong for the business. Getting backed into this kind of corner happens to companies in a position of weakness, not strength.

On the other hand, companies that are in a position of strength – the kind of strength that attracts professional investors, are in a position to negotiate terms that are either acceptable, or they know they can walk away and get better terms elsewhere. Worrying about falling pretty to the VC model is victim mentality.

- There is no secondary market for STOs, and if/when there are, it would over-regulate (KYC checks and disclosure filings) and levy fees.

Exchanges have started coming online (tZero, Blocktrade and Open Finance) and more secondary markets are developing. As they do, putting in place disclosure requirements and other investor protection policies is not a bad thing. On the contrary, creating a transparent trading environment is critical to developing a stable, liquid market.

- It would be impossible for any one exchange to be able to service clients on a global scale in the STO market.

How is it an indictment on STOs that multiple exchanges would be operate globally to service STO offerings, rather than a single, monolithic exchange? This is hardly a complaint that an ICO evangelist can level against STOs, given the burgeoning number of exchanges set up for ICO listings.

- Ultimately you have register an STO with a governing body (which they love).

The appeal to escape the grips and coercive compliance associated with regulatory and oversight bodies at any cost is steeped in ideology and totally lacks practicality and prudence, as well as any empirical basis that a totally unregulated economy is actually sustainable (just look at recent performance in the ICO markets). Registrations under the oversight of a securities exchange are voluntary. In the legacy capital markets, companies make a decision, un-coerced, to register their offerings and submit to other disclosure requirements because they believe there is a benefit that doing so will bring benefits that outweigh any drawbacks.

One of the most obvious benefits to transparent, orderly markets is that they facilitate greater participation from retail investors as well as professionals, which in turn, supports more liquidity.

- Filing paperwork with an authority removes decentralization. You cede control, in addition to the privacy of your stakeholders.

What kind of control, and what extent of control is effectively lost in the registration process? Regulatory bodies of exchanges certainly don’t presume to influence boards, C-suites and their businesses. Their interest is in creating orderly markets that facilitate capitalization for issuers and capital appreciation for investors. And the gambit issuers have historically adhered to that it is worth some oversight and administration for the opportunity to gain access to a broader base of investors. The gambit investors adhere to is that regulated exchanges will ensure that they get a fair shake.

- If you can’t stomach the risk of ICOs in return for, amongst other things, the promise of maintaining control of your company, don’t do an STO, just do a public offering.

This last point of criticism is the perfect segue to make the case for the positive characteristics of securities tokens offerings, or “Equity 3.0.”

The traditional capital markets are not broken by any means. In 2017 all major US indices hit record highs. IPO returns averaged 27%. 181 IPOs raised $44.2 billion, a 77% increase in volume and a 105% increase in value from 2016. A total of 737 follow-ons raised $142 billion in 2017. In the high-yield markets, 511 deals raised $277 billion, up 41% in activity from 2016.

Just this week, the National Venture Capital Association reported that there was more than $27.9 billion invested in U.S. companies in Q3, and $84.3 billion year-to-date, up rom $82.02 billion in all of 2017.

That’s good news. But the situation for start-ups, early-stage and emerging growth companies has been more challenging.

Amongst angel & seed deals, capital invested slipped from $2.1 billion to $1.6 billion in Q3, with deal count sliding from 1,005 to 785 deals – both on a sequential basis. Access to capital has never been easy for early stage companies, despite the contribution small businesses make to the U.S. economy.

Enter the JOBs Act…

In response and reaction to less access to capital for early stage issuers and virtually no access to investment opportunities amongst retail investors, Congress attempted to open up the markets for all stakeholders, introducing Reg D Rule 506(c), Reg CF and Reg A+.

The promise of the rise of crowdfunding was that it would open up access to capital for entrepreneurs and up-starts by allowing them to broadly solicit their offerings to the masses, sans the intermediaries, while allowing the masses, which had previously been prohibited from participating in risk capital investment due to their lack of accreditation and access to the network of early, venture-stage deals that had been the wheelhouse of venture capital and institutional investors.

In addition, by cutting out the middlemen and going direct, issuers could reduce their cost of capital.

The results have been mixed at best. Issuers with little experience raising capital have struggled with practical and technical direct public offering mechanics, structuring and packaging their offerings and getting their offerings in a public-facing environment sufficiently populated by qualified investors to have a realistic chance of capitalizing their plans.

2017 Annual US Capital Markets Watch. PWC.

Meanwhile, investors have been challenged with jumping through hurdles to demonstrate they are accredited (the verification process) or constraints limiting their participation levels – depending on the particular variety of crowdfunding they were dealing with.

The Reg A+ has gained more support. The framework provides issuers with broader access to investors (both accredited and non-accredited) and increases limitations on amounts that can be raised when non-accredited investors participate. Investors like them because more can participate, and the unaccredited amongst them are unencumbered by investment limits. But for these benefits issuers still complain about the costs, complications and time related to the process.

…And Crypto Offerings

The initial coin offering had immediate appeal to those that were comfortable transacting in basically unregulated markets. In addition to the lack of regulation, it required little in the way of disclosure; nothing in the way of diluting capitalization tables; strong demand for speculators on the expectation of a short path to liquidity.

Companies rushing to the ICO market quickly drafted white papers, created multiple round offerings (aka “Pre-Sales”) designed to gin-up demand and “FOMO” (fear-of-missing-out) amongst speculators which were quick to pass on diligence.

But in the U.S. ICOs came under increasing regulatory scrutiny. Security attorney William Restis describes the situation like this:

The problem was that, at least in the U.S., ICOs fall squarely within the ambit of federal and state securities laws. Basically, any fundraising tool, where investors expect to receive profits from the efforts of others, constitutes an offering of securities. And those securities cannot be sold or traded without registering the offering with the SEC or unless the offering is limited to “accredited investors”…Lawyers advising their ICO clients knew this. But because the SEC had not yet made a pronouncement, and no court had considered the issue, entrepreneurs didn’t care.”

Sugar, and sugar highs…sugar lows.

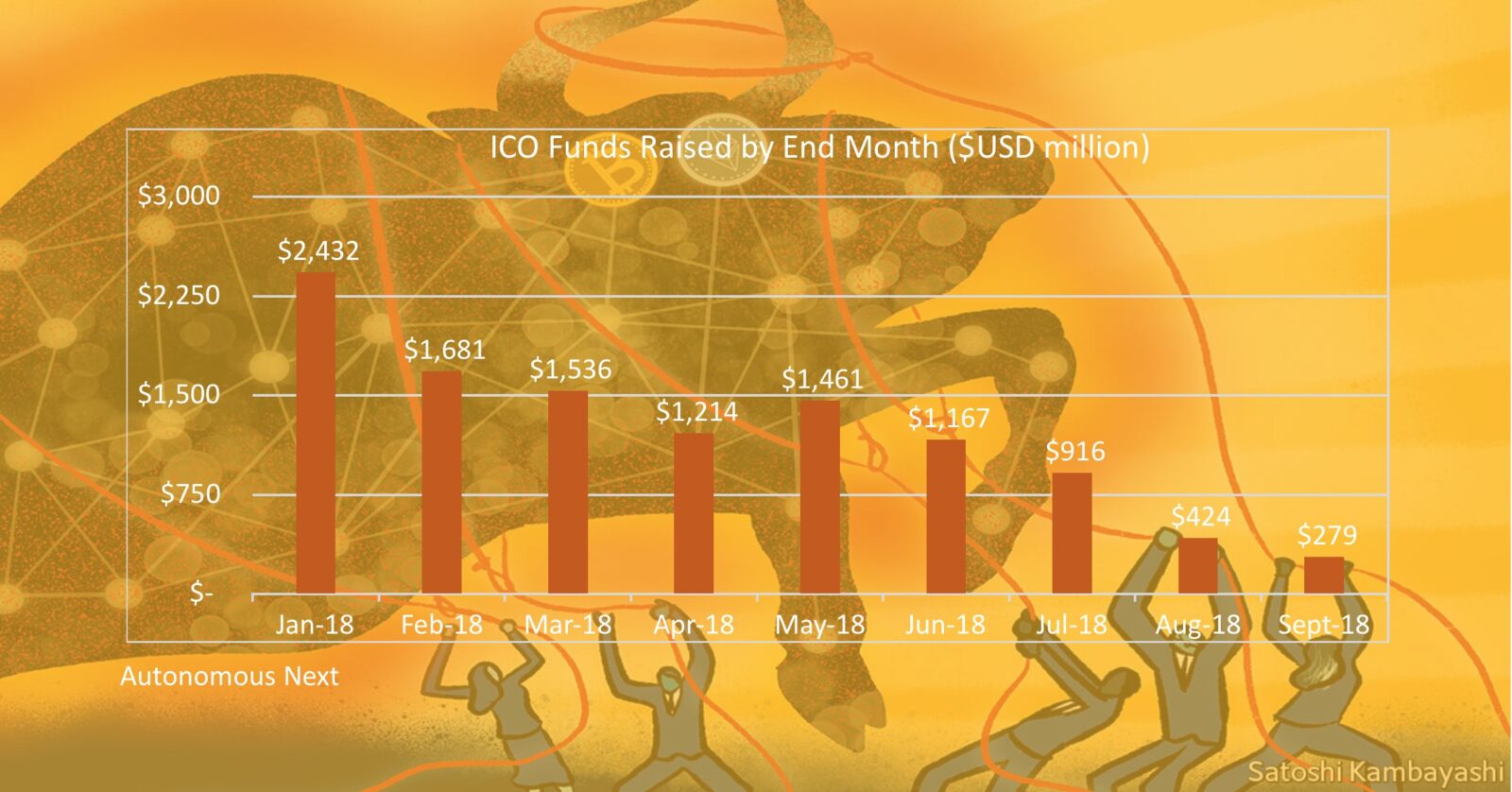

Amidst decline throughout 2018 in the value of cryptocurrencies, reports like those from the Statis Group that more than 80% of ICOs conducted in 2017 were scams and data from Coinopsy and DeadCoins finding that more than a thousand crypto projects are already “dead” as of June 2018, and pretty negative results of ICO performance, we saw a decline in ICOs to $3.6 billion in Q3 2018 from $9 billion the prior quarter.

ICO Rating’s Market Research Q2 2018 reported 50% of the ICO projects announced in Q2 of 2018 were not able to attract more than 100,000 USD and only 7% of all announced ICOs were able to be listed on exchanges. 55% of ICOs failed to complete their offerings. The median return from tokens in Q2 was -55.38%, compared to +49.32% in Q1. ROI after 3 days on an exchange in Q2 18 was -21.59% with 57% of tokens trading below the ICO price.

The ICO Is Dead – The Securities Token Offering is Next. February 15, 2018.

A report released this week from Autonomous Next said that ICO funding has dropped 90% since January 2018 to a 17-month low.

For most companies undertaking ICOs, selling tokens based on their utility always seemed like a stretch.

It has been a bit of a sideshow watching entrepreneur after entrepreneur twist into pretzels trying to make a case that utility tokens are really a value to stakeholders engaged purchasing goods and services from them. The real appeal was that ICO purchases would get in on the ground floor (pre-sale, etc.) of a staged offering with a series of “step-up” rounds with the promise of fast exits into an unregulated secondary market. Voilla.

No one has a crystal ball. It is impossible to predict where the ICO markets will wind up. But advocates of the next generation of crypto capitalization, securities token offerings, might be on to something. We think they are.

Security Tokens

We have heard STOs described as a safe, secure and sensible answer to the ICO. There is a lot to like about security tokens and security token offerings.

More likely to receive regulatory approvals. In terms of regulatory implications STOs have to register under Section 5 of the Securities Act of 1933 (the “Securities Act”) or an exemption has to be relied on. Exemptions include Regulation CF, Reg D Rule 506, Reg A and Reg S.

Flexible from a structuring standpoint. A security token can offer investors high yield or royalty payments, equity ownership, a hybrid scenario and utility characteristics.

Better for investors. First security tokens can provide investors with rights that are impoverished in utility token scenarios and there is less risk of the kind of information asymmetry prevalent in ICOs. While there isn’t a fast track to liquidity on a secondary exchange of the like we have seen with ICOs, the path to liquidity for security tokens sold in STOs is still reasonably efficient. And the oversight of STOs from the SEC and other regulatory bodies should provide investors some comfort of a lower chance of getting scammed.

Better for issuers. The fact that there is a regulatory framework governing the STO process is a good thing, and will lead to more reliable, stable markets over the long-run, which is critical for the function of any capital market. In addition, the potential audience of investors under an STO is arguably as large as it has ever been.

Security tokens should still appeal to proponents of ICOs and utility tokens, given the fact that they can claim the “democratization” of investment mantra. Issuers can use security tokens to raise capital without relying on investment banks and other intermediaries.

And a point that can’t be over emphasized is that security tokens, and the STO is well-suited to bring stability and credibility back to the crypto capital markets. The lack of regulation hurt the ICO markets. The STO ultimately combines the best of the capital markets with the potential of the cryptocurrency space.

For all of these reasons, we are bullish on the emerging STO market and its potential to continue the disruption – in a positive way – of the capital markets, improving the process for stakeholders throughout the value chain.